For more details on the research method, please see Chapters 1-6 in the book Parallaxic Praxis: Multimodal Interdisciplinary Pedagogical Research Design.

Chapter 7.2 is a synopsis of this project. Download sample chapters of the methodology here.

Chapter 7.2 is a synopsis of this project. Download sample chapters of the methodology here.

Methodological Research Design

Arts integrated research can be used to advance understanding by an artist-researcher independently, or by a research team collaborating with an artist. Interdisciplinary research accesses vocabulary, tools, techniques, methodologies, and theoretical frameworks from two or more specialized knowledge fields. Just as different academic disciplines each have their own ways of organizing and framing meaning, artistic disciplines (creative writing, visual arts, performing arts, film, new artistic practices, and more) also each have their own “language”. Interdisciplinary arts integrated work can expand innovation capacity by encouraging dialogues to develop among scholars with different strengths and different ways of framing the world (Sameshima, 2007; Sameshima, Vandermause, Chalmers & Gabriel, 2009). The term Arts Integrated Studies (AIS) is used to refer to research projects which use the arts as a generative mechanism in the research process.

Integrating the arts in research methodology affords scholars new lenses for viewing, analyzing, representing, and disseminating research (Sameshima, 2007). Just as mathematicians use bar graphs to demonstrate relationships between numeric data, artist-researchers render research data into stories, plays, documentaries, movies, paintings, posters, or poetry to better discern and represent relational connections. Art-making in the research process produces artefacts (plays, artworks) which can be purposefully used to mobilize knowledge across the audience spectrum and as teaching tools for students in formal and informal educational settings (Cole & Knowles, 2001). Using the arts to research and disseminate results is synergistic—humans make sense of the world through their writings, music, artworks, and various forms of representation (Barone & Eisner, 2012).

Integrating the arts as a teaching method in educational settings has demonstrated increased learning engagement and content knowledge (Burnaford, April & Weiss, 2000; Gelineau, 2004).

AIS require 1) theorizing through metaphors using theoretical frameworks in education, cultural studies, philosophy, psychology, history, and other disciplines; 2) strong foundational understandings of various traditional qualitative methods; and 3) personal artistic craft refinement or collaboration with arts experts. This theoretical framework is grounded in perspectives based on Stuart Hall’s (1973) notions on coding and encoding and Roland Barthe’s (1996) ‘polysemic’ (having different meanings) readings of texts—including non-word-based texts. AIS use a constructivist theoretical framework with a dynamic and multi-viewed approach. Constructivist epistemologies focus on schemata or knowledge systems that position knowledge generation as relational – that meaning occurs through interaction between experience and thought and that meaningful reality is socially constructed (Crotty, 2003). Thus, knowledge generation and meaning-making are always continual, ontological, and incomplete.

Integrating the arts in research methodology affords scholars new lenses for viewing, analyzing, representing, and disseminating research (Sameshima, 2007). Just as mathematicians use bar graphs to demonstrate relationships between numeric data, artist-researchers render research data into stories, plays, documentaries, movies, paintings, posters, or poetry to better discern and represent relational connections. Art-making in the research process produces artefacts (plays, artworks) which can be purposefully used to mobilize knowledge across the audience spectrum and as teaching tools for students in formal and informal educational settings (Cole & Knowles, 2001). Using the arts to research and disseminate results is synergistic—humans make sense of the world through their writings, music, artworks, and various forms of representation (Barone & Eisner, 2012).

Integrating the arts as a teaching method in educational settings has demonstrated increased learning engagement and content knowledge (Burnaford, April & Weiss, 2000; Gelineau, 2004).

AIS require 1) theorizing through metaphors using theoretical frameworks in education, cultural studies, philosophy, psychology, history, and other disciplines; 2) strong foundational understandings of various traditional qualitative methods; and 3) personal artistic craft refinement or collaboration with arts experts. This theoretical framework is grounded in perspectives based on Stuart Hall’s (1973) notions on coding and encoding and Roland Barthe’s (1996) ‘polysemic’ (having different meanings) readings of texts—including non-word-based texts. AIS use a constructivist theoretical framework with a dynamic and multi-viewed approach. Constructivist epistemologies focus on schemata or knowledge systems that position knowledge generation as relational – that meaning occurs through interaction between experience and thought and that meaningful reality is socially constructed (Crotty, 2003). Thus, knowledge generation and meaning-making are always continual, ontological, and incomplete.

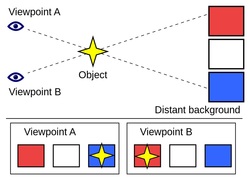

Figure 1. Parallax. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parallax

Figure 1. Parallax. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parallax

Parallax (see figure 1), as applied to a learning, teaching, gallery presentation, and research environment, is:

"the apparent change in location of an object against a background due to a change in observer position or perspective shift. The concept of parallax encourages researchers and teachers to acknowledge and value their own and their readers’ and students’ shifting subjectivities and situatedness which directly influence the construct of perception, interpretation, and learning" (Sameshima, 2007, p. 2).

"the apparent change in location of an object against a background due to a change in observer position or perspective shift. The concept of parallax encourages researchers and teachers to acknowledge and value their own and their readers’ and students’ shifting subjectivities and situatedness which directly influence the construct of perception, interpretation, and learning" (Sameshima, 2007, p. 2).

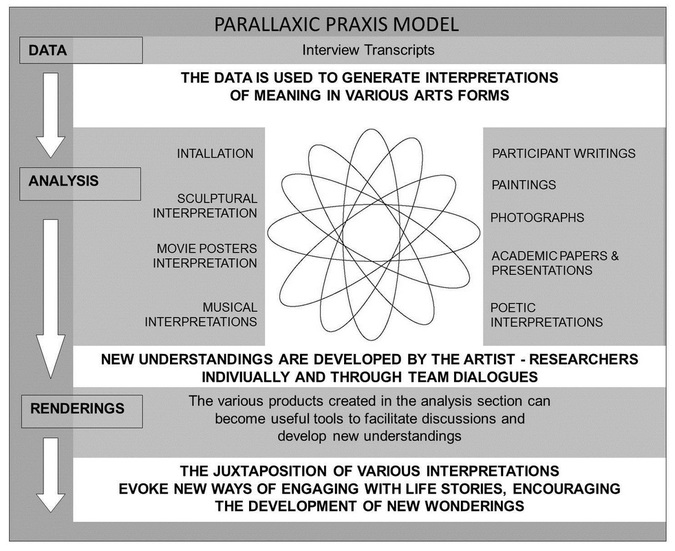

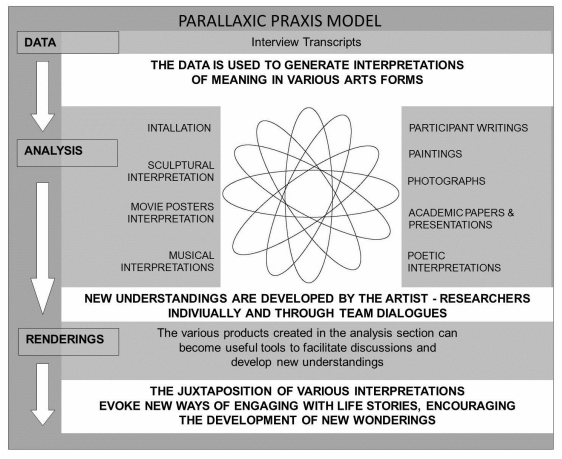

The Parallaxic Praxis model can be used both as an interdisciplinary research framework and as an educational framework in teacher education programs and formal K-12 settings to structure inquiry through dialogic and multi-modal means of accessing, engaging, and representing learning. There are three organizational phases in the model framework. In the Data Phase, researchers collect data in traditional and non-traditional ways. In the Analysis Phase, researchers from different fields interpret the data through various methodologies (a/r/tography, life writing, poetic inquiry) and mediums (theatre, music, poetry). The aim is to look at the data from various disciplines, lenses, and modalities as a means to complexify the interpretive possibilities and to generate collaborative dialogic analyses. In the Rendering Phase, the completed artefacts created during the previous phase are then used as juxtaposed touchstones for the interdisciplinary team to discuss their analyses, methodological processes, and creative practices. As well, these artefacts can be used as teaching tools in formal and informal education settings to mobilize knowledge.

The analysis phase is thus a method of fractalling the boundaries of the original data collection. The process may also be used as a way to metaphorically view the data, thus opening up larger semantic fields for discussion particularly among broad community audiences and various stakeholders. Metaphors work by reordering the relations of a semantic field by mapping them onto the existing relations of another semantic field (Stern, 2000). “Translating” data into other modalities invokes polysemy (phrases and words having multiple meanings) and pluralism (multiple interpretive views). These renderings aim to provoke further rhizomatic understandings, challenge conceptions, and generate the emergence of more questions (Sameshima, Vandermause, Chalmers & Gabriel, 2009).

Interdisciplinary teams may use various coding techniques to find common themes within narrative or alternatively collected data sets. AIS teams may utilize arts-based research (Barone & Eisner, 2012); arts-informed inquiry methods (Cole & Knowles, 2001); poetic inquiry (Prendergast, Leggo & Sameshima, 2009); a/r/tography (Irwin, 2004), and more, to create interpretive artful renderings in response to the data collected or as a means to generate an enlarged research investigative field.

In the Parallaxic Praxis model, following the creation of “renderings”, researchers visually juxtapose and analyze the various multi-modal artefacts through dialogic practices called catechizations. Catechizations are tools to guide visual analysis. The word catechize means to question systematically or searchingly. These practices use questions and inquiries to propel dialog forward, inward and into new understanding through dialogue practices following methods and tenets used in Duoethnography (Norris, Sawyer & Lund, 2012, also see Sameshima, 2013). The catechizations work to create relational aesthetics through visual formations that create the structured conditions for an exchange or encounter between different narratives and dialogic interpretations as well as between the researcher, participant/subject, and the audience (Bourriaud, 2002). Messages are not open to any interpretation or translation whatsoever as each mode in the circuit limits possibility in the next level of interpretation. Through analysis, interpretation, and in answering the research questions, specific arts-integrated practices or catechizations guide phenomenological meaning-making and expansion of the semantic field.

The five catechizations that are used to frame discussions about artifacts are: Mimesis (relational), Palimpsest (depth), Intertexuality (breadth), Aporia (conditions), and Sorites (cumulative).

For further information, please contact Pauline Sameshima ([email protected]).

The analysis phase is thus a method of fractalling the boundaries of the original data collection. The process may also be used as a way to metaphorically view the data, thus opening up larger semantic fields for discussion particularly among broad community audiences and various stakeholders. Metaphors work by reordering the relations of a semantic field by mapping them onto the existing relations of another semantic field (Stern, 2000). “Translating” data into other modalities invokes polysemy (phrases and words having multiple meanings) and pluralism (multiple interpretive views). These renderings aim to provoke further rhizomatic understandings, challenge conceptions, and generate the emergence of more questions (Sameshima, Vandermause, Chalmers & Gabriel, 2009).

Interdisciplinary teams may use various coding techniques to find common themes within narrative or alternatively collected data sets. AIS teams may utilize arts-based research (Barone & Eisner, 2012); arts-informed inquiry methods (Cole & Knowles, 2001); poetic inquiry (Prendergast, Leggo & Sameshima, 2009); a/r/tography (Irwin, 2004), and more, to create interpretive artful renderings in response to the data collected or as a means to generate an enlarged research investigative field.

In the Parallaxic Praxis model, following the creation of “renderings”, researchers visually juxtapose and analyze the various multi-modal artefacts through dialogic practices called catechizations. Catechizations are tools to guide visual analysis. The word catechize means to question systematically or searchingly. These practices use questions and inquiries to propel dialog forward, inward and into new understanding through dialogue practices following methods and tenets used in Duoethnography (Norris, Sawyer & Lund, 2012, also see Sameshima, 2013). The catechizations work to create relational aesthetics through visual formations that create the structured conditions for an exchange or encounter between different narratives and dialogic interpretations as well as between the researcher, participant/subject, and the audience (Bourriaud, 2002). Messages are not open to any interpretation or translation whatsoever as each mode in the circuit limits possibility in the next level of interpretation. Through analysis, interpretation, and in answering the research questions, specific arts-integrated practices or catechizations guide phenomenological meaning-making and expansion of the semantic field.

The five catechizations that are used to frame discussions about artifacts are: Mimesis (relational), Palimpsest (depth), Intertexuality (breadth), Aporia (conditions), and Sorites (cumulative).

For further information, please contact Pauline Sameshima ([email protected]).